Ask 4 the Moon: Prince, freedom and fiction

By Lyndon Barrois Jr.

Though he has been gone for over a month, I have been unable to mourn until now, writing this piece as we approach what would have been his 58th birthday, June 7. Last fall, I had begun a drawing series of him as a way back into portraiture. Of course, there was no way to anticipate the sudden grief around that project. But I feel like this has been the best way, with words rather than perfect pictures, though I will probably try to do that too, as both were important in everything he did.

I am guessing that my initial lack of emotion is a consequence of celebrity death in the internet age, especially as a citizen of social media. Online, I witness every permutation of post-mortem praise that makes it all too apparent that there is no private joy. Like collective fandom--which, sadly has made me reluctant to attend many live shows in recent years--collective mourning is an uncomfortable, disturbing phenomenon. It reminds me that the artist I cherish is not mine alone. And while I knowingly appreciate and hope that everyone in the world recognizes how special the artist is, the snob in me doesn't want to see it. Doesn't want it rubbed in my face. And definitely doesn't want to hear about all the popular shit. It's selfishly possessive to feel that I can tell people why they are right, but with reasons only I can bring to their attention. Of course what I mostly want is for them to know and appreciate that my fandom is sincere. That it is not a trend or agreeable groupthink but a longstanding, investigative relationship, just as reverent as it is critical.

I know that Prince is not mine, nor are the depths of my affection for his work unique to me. Yet my reaction was at first a classic emotional progression through disbelief, anger, and despair: Is this true? This is bullshit! What am I going to do? This resolved finally in an anxious self-reflection about expressing those emotions: How can I let everyone know I am hurting...without looking competitive? Because that's what this is ultimately. The warped desire attached to celebrity always involves a kind of egocentric loop. Of course it's about the celebrity figure themselves, but it's really about our love for them. The most I have been affected by a celebrity death was when Jay Dee (J Dilla) passed away. I say significant because until then I have never understood the mourning of someone you do not actually know. I didn't know Prince. And there are much more intense fans of his than myself. It is through these fans that I became the fan I am. The one closest to me is my cousin EJ, who gifted me with the literary, audio, and visual material that provided a deep and complex understanding of Prince's process, relationships, personality, and exhaustive productivity. EJ was the first person I thought of when I heard the news:

April 21, 12:37: "Cuzzin..." my message read. I waited almost an hour for his reply: "Man." "What now?" I asked. April 21, 13:29: "Open the Vault." April 21, 13:31, I texted back: "I don't think we're ready."

My parents had me at 19 and from what I can assume about their youth, in holding on to their coolness, I was experiencing things as they were. There wasn't this rift between their music and mine (that came much later). The popular music I heard through them was actually on point. It wasn't a matter of rediscovering something my generation didn't understand but appreciating culturally influential material in real time. Prince was a large part of this. I was often reminded of an incident that took place few years before I was born. A story of my father, his own legend inspired by the legendary, his lip syncing the song "Do It All Night" (Dirty Mind, 1980) at his high school talent show. He and two of his friends, posing at Dez Dickerson and Andre Cymone, appeared with mock instruments that my father had crafted from plywood. At the start of the first verse, to show that he had completed Prince's look from the album cover, he dropped his trench coat to reveal nothing but underwear and stockings and a handkerchief around his neck. The administration was so outraged they attempted to call the group off of the stage, but the crowd was rocking so hard that all protest was drowned out and the boys were able to finish the set. This was New Orleans in 1980.

I can't say which were the first songs I heard. I remember hearing the Sign o' the Times cassette on road trips and being haunted by the content. It was a shift in being affected by music on a level beyond entertainment or the expected quiet-storm soul singles that were commonly associated with artists of color at the time. Hearing about "dying of a big disease with a little name" and being told what "horse" was code for freaked me out. Hearing a man speak of being a girlfriend as a means to express unyielding devotion was revelatory. And that's only two songs into the album. I suppose you could say that at four-years old, Prince's writing was my first lasting lesson in metaphor; he raised my suspicion that there could always be something lurking behind what was most immediately given. He had a way of embracing the dark and light, or rather, an understanding of bringing the dark into light.

Admittedly, I am not completely exempt from rediscovery. I hadn't realized how watermarked on my brain every song on Dirty Mind was (obviously), or how the complexity of Controversy (1982) and the second half of 1999 (1983) faded from memory. I had to teach myself that there was so much more to Around the World in a Day (1985), than the circus organs in "Paisley Park" that I loved so much. And despite what anyone tells you, Batman (1989) is a really good album. Aside from the literal surreality of hearing Prince in a comic book film, the concept of the soundtrack--shifting from character to character for each song--is just brilliant, and "Electric Chair" has one of the best written chorus I can think of. Clearly, Sign o' the Times isn't the only sentimental album for me, but it is among his releases that garner the fuzziest feelings and through which I can most clearly recall a particular time. It is also perfect. When I decided to give a deep listen to the entire Warner catalog during my first year of college, my appreciation moved from sentimental to more objective. Sign o' the Times isn't perfect in the sense that it's the album of all albums, just that its internal logic is so damn resolved. There is not a song that is out of step or extraneous in its contribution to the pace or sequence of the ride. It is an album where each song successfully plays a role and seems to have a sonic or narrative purpose within the overall dynamic. It is not my favorite Prince album, but it is perfect. Explaining why these two things don't line up for me would require more space than I have been given.

I write this in conjunction with gorging on the wealth of material that has been trickling out of the Vault since his passing. What I am enjoying most is the concert footage from the early 80s. In fact, I find that I am focusing more on live performances than studio stuff, probably as some sort of desperate resuscitation to keep him alive. I am still realizing how technically mature he was even then. Perhaps the true consideration of him as a great guitarist was delayed amidst the wardrobe and all the other wild shit he had going on. I can't help but think of how wild it would have been to be there. What it meant to see a young man of color thriving, seemingly without care. Seeming to be completely free. With Dirty Mind, he took a punk-inspired departure from disco, and while the album consists of short and neat pop songs, the stage allowed him to let loose with this instrument. Like Eddie Hazel before him and contemporaries like Jesse Johnson, he reminded everyone that the rock genre does not own the gesture of shameless guitar solos. He did however, stage a kind of black reclamation of musical virtuosity in the context of post-Hendrix rock, while subverting the genre altogether.

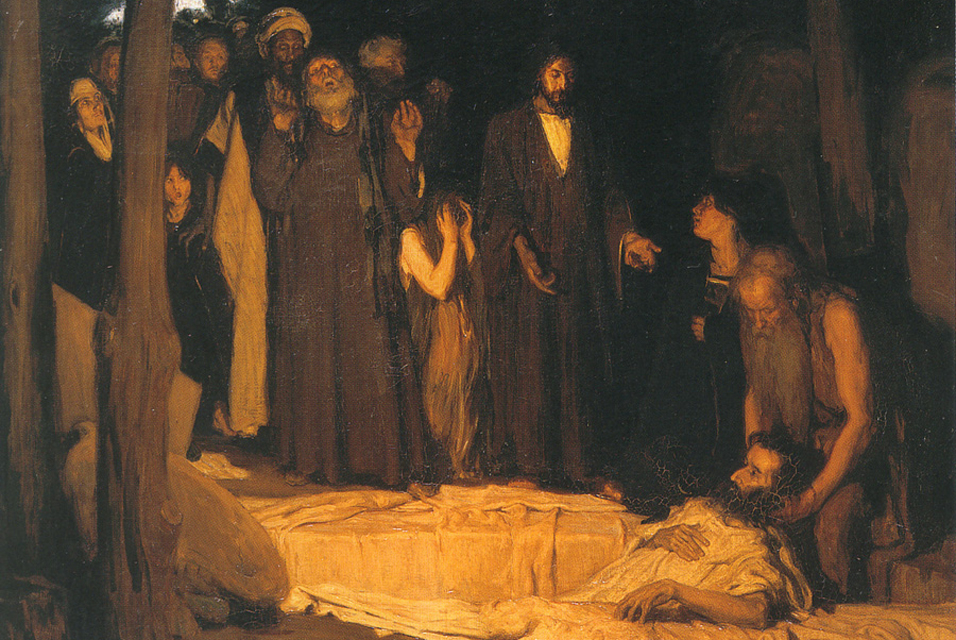

I can speak similarly about the early 20th century visual artist Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937), who dealt with religious painting in a socially constructive manner. Recognizing his adeptness as a figurative painter, he also challenged audiences with an entanglement of faith-based and secular realism, representing Biblical figures of Middle Eastern likeness instead of the Eurocentric standard. That relationship between spirituality and (sexual) secularity occupied much of Prince's writing, seemingly paradoxically so, surely just as absurdly as the presence of brown folks in Tanner's religious compositions at the time.

In watching an early performance from the Dirty Mind tour, I find myself wondering what genre of music would I suppose I were listening to. What would I think I was looking at? How are these blues chords performed in a manner outside of themselves? How long would it take to realize that it is not so much about the displacement of a sound as much as it is a disregard for distinct definitions of sound. It's as if he dresses genre in drag, showing both identities at once. Not a complete transformation, but hovering sweetly somewhere in between, like a cronut. He tore through stereotype, disrupting every expectation of how race corresponds to sound, how sound corresponds to action, or how each of these things are unsutured to a gendered body.

Given that I share his affinity for narrative imagery, my testimony would be quite incomplete without some mention of film. And the significance of Prince in the cinematic context is complex in a way that has expanded my understanding of the person and the music. He has been the star of three feature-length studio productions (a trilogy, I will soon argue), and has produced a series of concept albums that double as soundtracks (deepening the ficto-factual narrative that is his life). Recognizing Prince's relationship to narrative is super important, as it was applied to his life, the content of his writing, and ways in which the two swirl together. Which leads me to a perhaps not so radical, potentially absurd, but undoubtedly fun proposition: a theory that Under The Cherry Moon (1986) can be viewed as an unconscious sequel to Purple Rain (1984), positioning it as The Kid's feature-length cinematic dream sequence that follows the climactic resolve of the "Purple Rain" performance, and precedes the mature sage he embodies in Graffiti Bridge (1992).

A few things have led me to this line of thinking. The film is shot in black and white, which when done deliberately, usually signals a kind of alternate reality that is out of time. It is set abroad, though still in proximity to the sea, transporting our protagonist (and us) from Lake Minnetonka to the French Riviera. It is as if The Kid's unconscious is envisioning an existence outside of his hometown, othered, and severed from the familiar expectations of him as an eccentric artist. Much like dreams in which you are confusingly intimate with those you detest, Jerome resurfaces as his brother Tricky. After all, would there be any other context in which his ally would be his nemesis's sidekick? Finally, Christopher Tracy is an amalgamation of the Kid and Morris, embracing both the sly, coy, manipulative romanticism of The Kid, and the cool, overtly masculine bravado of Morris.

The actual Prince and Morris were good friends, and judging from recorded outtakes of jam sessions, they had similar approaches to humor and a similar way of putting-it-on when it came to character. Though Prince's position allowed him to cast Morris as the less ambiguous, fixed identity that he couldn't be. In turn, Prince and the Revolution exercised a kind of boundlessness not found in Morris Day & the Time, which allowed the former to access an open and roaming sensibility of sound versus clear categorization. Cinematically, it would seem that the Kid/Morris binary was a bit too limiting for Prince's projection of self. With the care placed in his image, the rarity of interviews, and the already confusing signals he exhibited, the public understanding of Prince was primarily through his music, videos, and live performances. With the close alignment of the film to what we were given in real life, Purple Rain had the effect of a true biopic, and I would imagine that the comedic trickster in him felt stifled by the reserved cool of The Kid.

Christopher Tracy becomes a strident example of American black plurality--able to exhibit a queer masculinity while at the same time carrying the conditions of urban American blackness that results in a very rare, yet desirably nuanced representation. He is everything that Prince (and an unconscious Kid) hoped to embody--a charming and talented outsider navigating a world that neither understands nor expects much of him. A black man with a fluid sense of dress, equally capable of classical piano serenades as he is misogynist hood antics.

Ironically, in light of this proposition, Purple Rain and, by proxy, Graffiti Bridge are the fantasy narratives, as they are primarily films about artists working through their creativity. There is not much questioning of class, race, or gender in the gloriously progressive Minneapolis we see on screen. Exceptions to these rules are the norm. The freaks run the show. The self-titled characters are mostly dramatizations of the artists themselves with a Gaussian blur between fact and fiction, underlined by the unmentioned visualization of Prince's biracial myth. The infamous White Cloud guitar is a virtual Excalibur, cutting through the time and space of the film, breaking the fourth wall into our lived reality.

Flanked on either side by musicals--one that doesn't feel like a musical and another that very much does--Under the Cherry Moon is ultimately a love story in which all of these issues of social and cultural hierarchy get addressed head on. Regardless of how much fun Christopher and Tricky have, no matter how much agency they exercise on foreign soil, they (and we) are frequently reminded of their race, complexion, nationality, class, and weird clothes. Now, you could be saying, "Nahhh Lyn, Prince was just doing his Bela Lugosi-slapstick-Casablanca-French New Wave thing only with black folks. . . " (which it is) but I would argue that in these meta-representations of himself, in two very different narrative contexts, Prince offers two sides of utopian coin that his whole program operates on: both a state of being that is free in spite of opposition and the construction of a world in which opposition to freedom does not exist.

It is worth mentioning that his Camille recording persona emerges around the time between Parade (1986) and Sign o' the Times. Prince himself credited Camille with the production of the initially unreleased Black Album (1987), which makes sense given the snarky lyrical content of songs featuring this voice. Singing some of the more complex commentaries on romance and relationships, the helium-pitched alter-ego of Camille can be heard in many iconic hits and peripheral classics ("Housequake," "If I Was Your Girlfriend," "Crystal Ball," "Rock Hard in a Funky Place," and many others) and is meant to be a vocal register embodying yet another androgynous symbolic representation. It adds to his ideology of radical inclusivity, eventually summed up in the inaudible symbol, not just as the marriage of male and female in the traditional sense, but the existence of a hybrid unit that creates space for identity to be assumed in a myriad of ways.

I continue to descend down the rabbit hole, courtesy of a purple pill. Delving into the side projects, outtakes, rehearsals, in attempts to get closer. It is during these moments of depth and exclusivity of all things Prince that I begin to feel a part of it. Like I could wear heels with my chest out and a chain around my waist. I forget for very brief moments that this is unlicensed behavior in the spaces I navigate. I am reminded that I contend with self-consciousness and, ultimately, fear. Prince contributed so much in the way of a liberated yet constructed (and inherited) black identity that I fail to understand why so many oppressive stereotypes have held firm. Why there is a cognitive dissonance in certain communities of thought, where collective praise for Prince from hardcore rappers (Tupac Shakur among them) rubs shoulders with a homophobia and a rampant fear of black male "feminization."

Nina Simone described freedom as having no fear. Does such a condition actually exist? Is the possibility within sight? And how much does it cost? As a child, I played with the plywood Telecaster that my father made for that three minutes of freedom on stage that day. When I look at photos of Prince, his bandmates, the sets they created, and when I watch them work, it appears that they have accessed this space. When in his world, they lived in it. A kind of utopic isolation that has to either ruin you or prepare you for anything. Prince has gone from being free in life to being free of life. Showing us that if we are willing, we can be free in the world until we are free of the world. Free to change our minds. Free to go almost anywhere, anytime. I am glad to have all that we got from him. I am glad that he is free.

To see more images of Prince altered by Mr. Barrois using the CMYK printing techniques similar to those he uses in his current CAM exhibit 'On Color,' click the image below. To read a recent interview with Lyndon by Seth Lewis, click here.